Economy of Scotland in the early modern period

The economy of Scotland in the early modern era encompasses all economic activity in Scotland between the early sixteenth century and the mid-eighteenth. The period roughly corresponds to the early modern era in Europe, beginning with the Renaissance and Reformation and ending with the last Jacobite risings and the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution.

At the beginning of this period Scotland was a relatively poor country, with difficult terrain and limited transport, relying on traditional agricultural methods of jointly run fermtouns and bailes. The late sixteenth century saw economic distress, inflation and famine, but also the beginnings of industrial production as new techniques were imported to the country. The seventeenth century saw economic development led by trade, particularly to England and with the Americas, despite the problems of tariffs. There was continued occasional famine, culminating in the "seven ill years" of the 1690s. Attempts to establish a Scottish colony in Central America as part of the Darién scheme ended in disaster in the 1690s. After the Union with England in 1707 there was increasing introduction of improvements in agriculture that helped improve the food supply and growing trade with the Americans that produced the Tobacco Lords of Glasgow, the trade in sugar and rum and Paisley in cloth. There was also the development of financial institutions, including the Bank of Scotland, Royal Bank of Scotland and British Linen Company, and improvements in roads both of which would help facilitate the Industrial Revolution that would accelerate in the late eighteenth century.

Sixteenth century

[edit]

Agriculture

[edit]Jenny Wormald has commented that, "to talk of Scotland as a poor country is a truism".[1] At the beginning of the era, with difficult terrain, poor roads and limited methods of transport, there was little trade between different areas of the country and most settlements depended on what was produced locally, often with very little in reserve in bad years. Most farming was based on the lowland fermtoun or highland baile, settlements of a handful of families that jointly farmed an area notionally suitable for two or three plough teams, allocated in run rigs, of "runs" (furrows) and "rigs" (ridges), to tenant farmers. They usually ran downhill so that they included both wet and dry land, helping to offset the problems of extreme weather conditions. Most ploughing was done with a heavy wooden plough with an iron coulter, pulled by oxen, which were more effective in the heavy Scottish soil, and cheaper to feed than horses.[2]

Trade

[edit]

From a low base at the beginning of the sixteenth century, trade expanded in the 1530s, but suffered from the English invasions of the Rough Wooing in the 1540s.[3] From the mid-sixteenth century, Scotland experienced a decline in demand for exports of cloth and wool to the continent. Scots responded by selling larger quantities of traditional goods, increasing the output of salt, herring and coal.[4] The fortunes of Scottish burghs in the export trade changed across the century. Haddington, which had been one of the major centres of trade in the late Medieval period, saw its share of foreign exports collapse in the sixteenth century. Aberdeen's share of trade remained stable for most of the century, but slumped in the last decade. The small Fife ports grew in significance and Edinburgh took an increasing share of trade through its port of Leith.[5] This forced smaller ports to diversify into other commodities and to undertake more coastal trading. Overall there was an increase in foreign trade from the 1570s, of which Edinburgh received the major share.[5]

Women and the economy

[edit]Women acted as an important part of the workforce. Many unmarried women worked away from their families as farm servants and married women worked with their husbands around the farm, taking part in all the major agricultural tasks. They had a particular role as shearers in the harvest, forming most of the reaping team of the bandwin. Women also played an important part in the expanding textile industries, spinning and setting up warps for men to weave. There is evidence of single women engaging in independent economic activity, particularly for widows, who can be found keeping schools, brewing ale and trading.[6]

Economic downturn and early industry

[edit]

The late sixteenth century was an era of economic distress, probably exacerbated by increasing taxation and the devaluation of the currency. In 1582 a pound of silver produced 640 shillings, but in 1601 it was 960 and the exchange rate with England was £6 Scots to £1 sterling in 1565, but by 1601 it had fallen to £12. Wages rose rapidly, by between four or five times between 1560 and the end of the century, but failed to keep pace with inflation. This situation was punctuated by frequent harvest failures, with almost half the years in the second half of the sixteenth century seeing local or national scarcity, necessitating the shipping of large quantities of grain from the Baltic,[7] referred to as Scotland's "emergency granary". This was particularly from Poland through the port of Danzig, but later Königsberg and Riga, shipping Russian grain, and Swedish ports, would become important. The trade was so important that Scottish colonies were established in these ports.[8] Distress was exacerbated by outbreaks of plague, with major epidemics in the periods 1584–88 and 1597–1609.[7]

There were the beginnings of industrial manufacture in this period, often utilising expertise from the continent, which included a failed attempt to use Flemings to teach new techniques in the developing cloth industry in the north-east, but more successful in bringing a Venetian to help develop a native glass blowing industry. George Bruce used German techniques to solve the drainage problems of his coal mine at Culross. In 1596 the Society of Brewers was established in Edinburgh and the importing of English hops allowed the brewing of Scottish beer.[9]

Seventeenth century

[edit]Economic expansion and customs tariffs

[edit]

In the early seventeenth century famine was relatively common, with four periods of famine prices between 1620 and 1625. The English invasions of the 1640s had a profound impact on the Scottish economy, with the destruction of crops and the disruption of markets resulting in some of the most rapid price rises of the century.[10] Under the Commonwealth, the country was relatively highly taxed, but gained access to English markets.[11] After the Restoration the formal frontier with England was re-established, along with its customs duties. Economic conditions were generally favourable from 1660 to 1688, as land owners promoted better tillage and cattle-raising.[4] The monopoly of royal burghs over foreign trade was partially ended by and Act of 1672, leaving them with the old luxuries of wines, silk, spices and dyes and opening up trade of increasingly significant salt, coal, corn and hides and imports from the Americas. The English Navigation Acts limited the ability of the Scots to engage in what would have been lucrative trading with England's growing colonies, but these were often circumvented, with Glasgow becoming an increasingly important commercial centre, opening up trade with the American colonies: importing sugar from the West Indies and tobacco from Virginia and Maryland. Exports across the Atlantic included linen, woollen goods, coal and grindstones.[4] The English protective tariffs on salt and cattle were harder to disregard and probably placed greater limitations on the Scottish economy, despite attempts of the King to have them overturned. Scottish attempts to counter this with tariffs of their own were largely unsuccessful, as Scotland had relatively few vital exports to protect. Attempts by the Privy Council to build up luxury industries in cloth mills, soap works, sugar boiling houses, gunpowder and paper works, also proved largely unsuccessful.[12] However, by the end of the century the drovers roads, on which black cattle were driven from the Highlands through south-west Scotland to north-east England, had become firmly established.[13]

Seven ill years

[edit]

The closing decade of the seventeenth century saw the generally favourable economic conditions that had dominated since the Restoration come to an end. There was a slump in trade with the Baltic and France from 1689–91, caused by French protectionism and changes in the Scottish cattle trade, followed by four years of failed harvests (1695, 1696 and 1698-9), known as the "seven ill years".[14] The result was severe famine and depopulation, particularly in the north.[15] The famines of the 1690s were seen as particularly severe, partly because famine had become relatively rare in the second half of the seventeenth century, with only one year of dearth (in 1674) and the shortages of the 1690s would be the last of their kind.[12] The Parliament of Scotland of 1695 enacted proposals that might help the desperate economic situation, including setting up the Bank of Scotland. The "Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies" received a charter to raise capital through public subscription.[14] Recently founded sugar houses producing sugarloaves and rum with imported sugar were encouraged in Glasgow and Leith.[16]

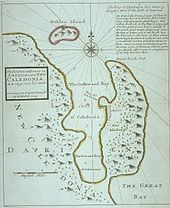

Darién Scheme

[edit]The "Company of Scotland" invested in the Darién scheme, an ambitious plan devised by William Paterson, the Scottish founder of the Bank of England, to build a colony on the Isthmus of Panama in the hope of establishing trade with the Far East.[17] The Darién scheme won widespread support in Scotland as the landed gentry and the merchant class were in agreement in seeing overseas trade and colonialism as routes to upgrade Scotland's economy. Since the capital resources of the Edinburgh merchants and landholder elite were insufficient, the company appealed to middling social ranks, who responded with patriotic fervour to the call for money; the lower orders volunteered as colonists.[18] However, both the English East India Company and the English government opposed the idea. The East India Company saw the venture as a potential commercial threat and the government were involved in the War of the Grand Alliance from 1689 to 1697 against France and did not want to offend Spain, which claimed the territory as part of New Granada and the English investors withdraw. Returning to Edinburgh, the Company raised £400,000 in a few weeks. Three small fleets with a total of 3,000 men eventually set out for Panama in 1698. The exercise proved a disaster. Poorly equipped; beset by incessant rain; suffering from disease; under attack by the Spanish from nearby Cartagena; and refused aid by the English in the West Indies, the colonists abandoned their project in 1700. Only 1,000 survived and only one ship managed to return to Scotland.[17] The cost of £150,000 put a severe strain on the Scottish commercial system and led to widespread anger against England, but also highlighted the problems of maintaining two economic policies, increasing pressure for full union.[19]

Early eighteenth century

[edit]Agricultural improvement

[edit]

At the Union of 1707 England had about five times the population of Scotland, and about 36 times as much wealth, however, Scotland began to experience the beginnings of economic expansion that would begin to allow it to close this gap.[20] Contacts with England led to a conscious attempt to improve agriculture among the gentry and nobility. Haymaking was introduced along with the English plough and foreign grasses, the sowing of rye grass and clover. Turnips and cabbages were introduced, lands enclosed and marshes drained, lime was put down, roads built and woods planted. Drilling and sowing and crop rotation were introduced. The introduction of the potato to Scotland in 1739 greatly improved the diet of the peasantry. Enclosures began to displace the runrig system and free pasture. The Society of Improvers was founded in 1723, including in its 300 members dukes, earls, lairds and landlords. There was increasing regional specialisation. The Lothians became a major centre of grain, Ayrshire of cattle breading and the Borders of sheep. However, although some estate holders improved the quality of life of their displaced workers, enclosures led to unemployment and forced migrations to the burghs or abroad.[21]

Trade and industrialisation

[edit]

The major change in international trade was the rapid expansion of the Americas as a market.[22] Glasgow supplied the colonies with cloth, iron farming implements and tools, glass and leather goods. Initially relying on hired ships, by 1736 it had 67 of its own, a third of which were trading with the New World. Glasgow emerged as the focus of the tobacco trade, re-exporting particularly to France. The merchants dealing in this lucrative business became the wealthy tobacco lords, who dominated the city for most of the century. Other burghs also benefited. Greenock enlarged its port in 1710 and sent its first ship to the Americas in 1719, but was soon playing a major part in importing sugar and rum.[23]

Cloth manufacture was largely domestic. Rough plaids were produced, but the most important areas of manufacturing was linen, particularly in the Lowlands, with some commentators suggesting that Scottish flax was superior to Dutch. The Scottish members of parliament managed to see off an attempt to impose an export duty on linen and from 1727 it received subsidies of £2,750 a year for six years, resulting in a considerable expansion of the trade.[24] These funds were derived from the Board of Trustees for Fisheries and Manufactures in Scotland, using money set aside at the Union. It distributed £6,000 a year to encourage industry, particularly the linen industry and fishing.[25] Paisley adopted Dutch methods and became a major centre of production. Glasgow manufactured for the export trade, which doubled between 1725 and 1738. The move of the British Linen Company in 1746 into advancing cash credits also stimulated production. The trade was soon being managed by "manufacturers" who supplied flax to spinners, bought back the yarn and then supplied to the weavers and then bought the cloth they produced and resold that.[24]

Banking also developed in this period. The Bank of Scotland was suspected of Jacobite sympathies and so a rival Royal Bank of Scotland was founded in 1727. Local banks began to be established in burghs like Glasgow and Ayr. These would make capital available for business and the improvement of roads and trade, which would help create the conditions for the Industrial Revolution that accelerated in the second half of the century.[26]

Notes

[edit]- ^ J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, p. 41.

- ^ J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 41–55.

- ^ I. D. Whyte, "Economy: 1500–1770", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 197–8.

- ^ a b c C. A. Whatley, Scottish Society, 1707–1830: Beyond Jacobitism, Towards Industrialisation (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), ISBN 071904541X, p. 17.

- ^ a b M. Lynch, "Urban society, 1500–1700" in R. A. Houston and I. D. Whyte, Scottish Society, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0521891671, pp. 99–101.

- ^ R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, pp. 86–8.

- ^ a b J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 166–8.

- ^ H. H. Lamb, Climatic History and the Future (London: Taylor & Francis, 1977), ISBN 0691023875, p. 472.

- ^ J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 172–3.

- ^ R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0415278805, pp. 291–3.

- ^ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 226–9.

- ^ a b R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0415278805, pp. 254–5.

- ^ R. A. Houston, Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), ISBN 0521890888, p. 16.

- ^ a b R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0415278805, pp. 291–2 and 301-2.

- ^ K. J. Cullen, Famine in Scotland: The “Ill Years” of the 1690s (Edinburgh University Press, 2010), ISBN 0748638873.

- ^ T. C. Smout, 'The Early Scottish Sugar Houses, 1660-1720', Economic History Review, 14:2 (1960), pp. 240–253.

- ^ a b E. Richards, Britannia's Children: Emigration from England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland since 1600 (Continuum, 2004), ISBN 1852854413, p. 79.

- ^ D. R. Hidalgo, "To Get Rich for Our Homeland: The Company of Scotland and the Colonization of the Darién", Colonial Latin American Historical Review, 10:3 (2001), p. 156.

- ^ R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0415278805, p. 314.

- ^ R. H. Campbell, "The Anglo-Scottish Union of 1707. II: The Economic Consequences", Economic History Review, vol. 16, April 1964.

- ^ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 288–91.

- ^ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, p. 292.

- ^ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, p. 296.

- ^ a b J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 292–3.

- ^ B. Bonneyman, "Agrarian patriotism and the landed interest: the Scottish 'the Society of Improvers in the Knowledge of Agriculture' 1723–46", in K. Stapelbroek, J. Marjanen, eds, The Rise of Economic Societies in the Eighteenth Century: Patriotic Reform in Europe and North America (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), ISBN 1137136308, p. 92.

- ^ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, p. 297.